While researching Soviet WWII history, I came across reference to bicycle brigades used by the Germans as part of the siege of Leningrad (St. Petersburg). Evidently, the bicycle infantryman was seen as a replacement for the cavalry messenger and able to transport supplies in places where truck and tank travel was impossible. There’s a whole lengthy history here (including pics of folding bicycles in action). So, maybe another antecedent for my current trip.

Category Archives: Observation

Tour Envy

Mikhail Bakhtin

Mikhail Bakhtin’s house and lovingly curated museum in Oryol. Bakhtin is a favorite of literary and film theorists and is famous for his books on Dostoevsky and Rabelais. Unfortunately, his ideas on freedom of the individual did not make him a favorite of the Soviets and he faced several exiles and difficulty in publishing (and even getting his dissertation accepted). I received a private tour from a woman who spoke lovingly of her friend Misha.

Nizhyn

On Chernobyl, Fear and Transparency

I visited the remains of the Chernobyl power plant and surrounding 30km radial exclusion zone today. Originally, I wanted to bike to the zone but permitting proved impossible (the only official in Ukraine capable of issuing permits is on vacation until July) and it was unlikely I would be allowed to actually bike within the secure perimeter. Unlike other two-wheel attempts at Chernobyl, I will not pretend to have bicycled but instead just present photos and my impressions from a visit with an official government guide.

I was seven years old in 1986 when Chernobyl Reactor #4 exploded and it is one of my first memories of a “news” event. Today, the disaster is synonymous with the Prometheus myth made real and jokes about three-eyed fish and Char-Nobyl. If you tell most Ukrainians about visiting the region, they still react in horror and caution you against the danger.

However, it turns out the Chernobyl region isn’t a barren wasteland. Instead, with human activity at a minimum, nature has come back with a vengeance. The Red Forest of charred trees has been replaced with verdant greens and (as my arms can attest) a whole lot of bugs. In the absence of human predators, animals are thriving including a large herd of wild boar and reports of giant 50kg catfish living in the nuclear cooling pools (not mutants, catfish live ~80 years and continually grow).

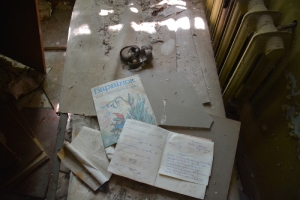

Pripyat, the largest city in the zone with pop. ~50,000 in 1986, is only 3km from the Chernobyl plant and was built in 1970 to house the Chernobyl workers. It was only inhabited for a short 16 years before being mass evacuated two days after the reactor suffered partial meltdown. The buildings remain as a ghost town (although most of the human belongings were looted in the 90s when USSR collapsed), and Pripyat is the site of an iconic Amusement Park and Ferris Wheel (featured in nearly full detail in Call of Duty 4 among many music videos, films, etc) which never reached its planned grand opening on May 1, 1986 five days after the disaster.

And, humans can indeed live within the zone although with precautions. A team of 3000 workers inhabit the town of Chernobyl to continue managing the plant’s liquidation process. While the soil, plants and food within the inner 10km zone are radioactive and dangerous to ingest, the background radiation from a day at Chernobyl is nearly equivalent with a chest x-ray. Most workers spend 50% of their time in the zone and the remainder offsite to keep their doses within government prescribed levels and wear badges to measure their exposure at all times. They actually seem to enjoy living in Chernobyl surrounded by nature and a bit removed from the hectic life of our “normal” cities.

And, humans can indeed live within the zone although with precautions. A team of 3000 workers inhabit the town of Chernobyl to continue managing the plant’s liquidation process. While the soil, plants and food within the inner 10km zone are radioactive and dangerous to ingest, the background radiation from a day at Chernobyl is nearly equivalent with a chest x-ray. Most workers spend 50% of their time in the zone and the remainder offsite to keep their doses within government prescribed levels and wear badges to measure their exposure at all times. They actually seem to enjoy living in Chernobyl surrounded by nature and a bit removed from the hectic life of our “normal” cities.

Which brings up what to me is the central paradox of nuclear energy disasters: To avoid panic, government and nuclear officials keep information (and more importantly) data secret. The effects are to put workers and those in close proximity to the disaster in danger while needlessly scaring larger populations who often form unfounded beliefs about radiation danger in the absence of trustworthy sources.

In the case of Chernobyl, Ukrainians still believe today that even while 3000 scientific workers inhabit Chernobyl the zone is only full of death, danger and destruction for anyone who approaches. Yet, in 1986 at the time of the disaster, firemen rushed into the plant (and to their deaths) within two minutes of the initial explosion with no training or knowledge of nuclear safety. And children and others at high risk from radiation poisoning in surrounding areas were unable to take straightforward precautions (stay indoors, ingest iodine tablets) because government officials were unwilling to disclose the event in a timely fashion.

Unfortunately, Fukushima indicates that these lessons still haven’t been learned.

While I don’t know enough about nuclear safety to comment on the robustness of disaster planning at contemporary plants, it is clear that scientists still fail to contemplate the risk of unanticipated events (e.g. tsunamis). More chilling is that governments still opt for secrecy over transparency. Even though scientific experts agree that those who live far distances from Fukushima will likely not face increased radiation risk, the public-at-large is still very afraid.And, maybe they have a reason to be. If governments fail to be transparent and open with data in the face of large-scale nuclear disaster, it makes it very difficult to build trust with the public. Radiation danger is invisible and confusing to people. By keeping data secret, governments don’t reduce panic, they reduce trust and create irrational fear.