While I have been taught about the horrors of the Holocaust since the days of Wednesday afternoon Hebrew School, I have never visited a concentration camp. I have seen the piles of shoes in the DC Holocaust museum. I have read the names of those who were lost. But, I have never been to such an evil place as Terezin.

“Work will make you free” slogan painted over the entrances to many camps

Jewish education has created a curriculum that effectively communicates the enormity of the Holocaust. By taking abstract numbers like 6 million and rendering them physical (shoes, names intoned, Anne Frank’s Diary), the Jewish community tries to pass down the sheer scale of suffering and death faced by a community for those who were lucky enough not to be there. But, for me as an American Jew whose family emigrated from Europe well before WWII, it was the sense of place, of being there which had the greatest impact.

History

Doors leading to solitary confinement cells in the Small Fortress

Terezin is an evil place. Located about 70km north of Prague in the Czech Republic along the Elbe river, the entire town is a walled fortress built by the Hapsburg’s in 1780 for the purposes of war. I visited on my last leg while spending the night in Litoměřice across the river. To give you a sense of evil, even if we subtract the years from 1940-1945 when Terezin was used as a staging and starvation camp for Jews on their way to death sites, we are left with the following:

• Two days after the end of the Austro-Prussian War, the entire Terezin garrison unaware the war was over, attacks and destroys the Neratovice bridge.

• The small fortress in Terezin is used as a solitary confinement prison for political prisoners during WW1.

• Gavrilo Princip, assassin of Archduke Franz Ferdinand (and if you believe your 5th grade history progenitor of WWI), dies in 1918 from Tuberculosis as a prisoner in cell #1 at Terezin.

• After WWII ends and the Jews in Terezin are liberated, the camp is overrun with disease and quarantined with over 30% of the survivors dying.

• After WWII ends and the Jews in Terezin are liberated, the camp is overrun with disease and quarantined with over 30% of the survivors dying.

• Once the Jews leave, the Czechs turn the small fortress into a prison and torture chamber for revenge on Nazis and ethnic Germans on their return from occupied lands to Germany.

Which brings us to WWII. Terezin (called Theresienstadt by the Germans) was meant to be a forced Jewish ghetto for Jews of “privilege” (distinguished WWI service, ties to the West, cultural importance, elderly, Jews married to Aryans). A gas chamber was built in Terezin at the end of the war but never used. Instead, death in the camp came from starvation, disease and torture. Those that survived were shipped to actual death camps such as Auschwitz. Less than 5% of the Jews forced to live in Terezin ultimately survived.

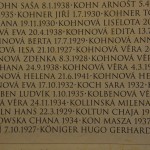

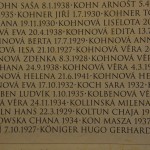

Terezin is often remembered for its cultural artifacts. Most harrowing are the drawings made by children during clandestine art lessons. A large collection are displayed in the Terezin Ghetto Museum and Prague’s Jewish Museum. The Nazis tried to use the camp for propaganda purposes, spending much effort on sprucing the camp up to fool Red Cross inspectors in 1944 and producing a “documentary” film intending to show the world how much the Jews were flourishing under German internment. About 20 minutes of the film exist, and I was able to have a private showing in Terezin. The original soundtrack is replaced by the intonement of transports from the camp and ultimate survival records (“Transport AA. 3304 to Auschwitz, 5 survivors”). The combination of the film, the voice and the empty theater was chilling.

Terezin is often remembered for its cultural artifacts. Most harrowing are the drawings made by children during clandestine art lessons. A large collection are displayed in the Terezin Ghetto Museum and Prague’s Jewish Museum. The Nazis tried to use the camp for propaganda purposes, spending much effort on sprucing the camp up to fool Red Cross inspectors in 1944 and producing a “documentary” film intending to show the world how much the Jews were flourishing under German internment. About 20 minutes of the film exist, and I was able to have a private showing in Terezin. The original soundtrack is replaced by the intonement of transports from the camp and ultimate survival records (“Transport AA. 3304 to Auschwitz, 5 survivors”). The combination of the film, the voice and the empty theater was chilling.

Impressions

But, most chilling was just wandering through the deserted town. Well, the first shock is that the town isn’t actually deserted. A handful of people still seem to live there. So, as I bicycled into the fortress, there was a family playing on the lawn and a few old men walking on the streets. I can’t imagine what it would be like to live in a place with Terezin’s history and being confronted with it every day by every building and every visitor to your town.

But, most chilling was just wandering through the deserted town. Well, the first shock is that the town isn’t actually deserted. A handful of people still seem to live there. So, as I bicycled into the fortress, there was a family playing on the lawn and a few old men walking on the streets. I can’t imagine what it would be like to live in a place with Terezin’s history and being confronted with it every day by every building and every visitor to your town.

There are several museums and a loose tour of buildings. While ghost town evil pervades the entire town, bicycling over the dry moat to the small fortress adds both a sense of size (it’s a good 5 minute ride) and confinement as you are now standing inside a massive prison built inside an even larger prison.

As opposed to the Jewish Quarter in Prague, there are almost no other tourists which greatly adds to the solemnity of the experience. With few signs and almost no staff, you are left to explore the prison space on your own. I actually bicycled through the main gate and into the prison yard before being requested to leave the bike at the entrance our of respect for the place. I totally understand, but I also felt that a Jew bicycling freely around a space the Nazis intended as the heart of their master plan was maybe one of the best statements I could make.

As opposed to the Jewish Quarter in Prague, there are almost no other tourists which greatly adds to the solemnity of the experience. With few signs and almost no staff, you are left to explore the prison space on your own. I actually bicycled through the main gate and into the prison yard before being requested to leave the bike at the entrance our of respect for the place. I totally understand, but I also felt that a Jew bicycling freely around a space the Nazis intended as the heart of their master plan was maybe one of the best statements I could make.

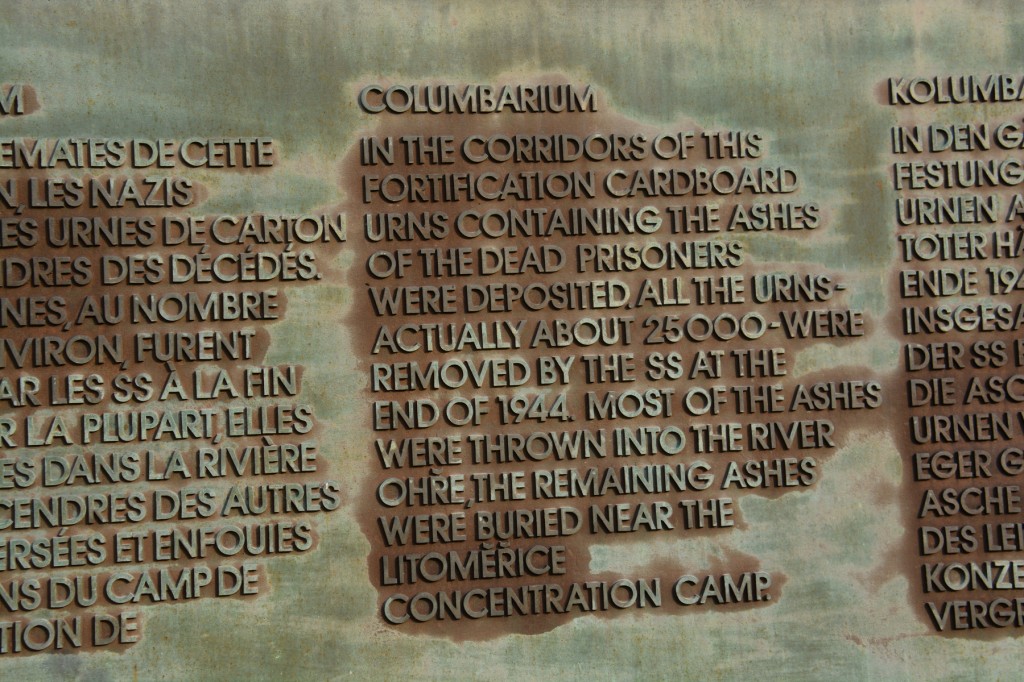

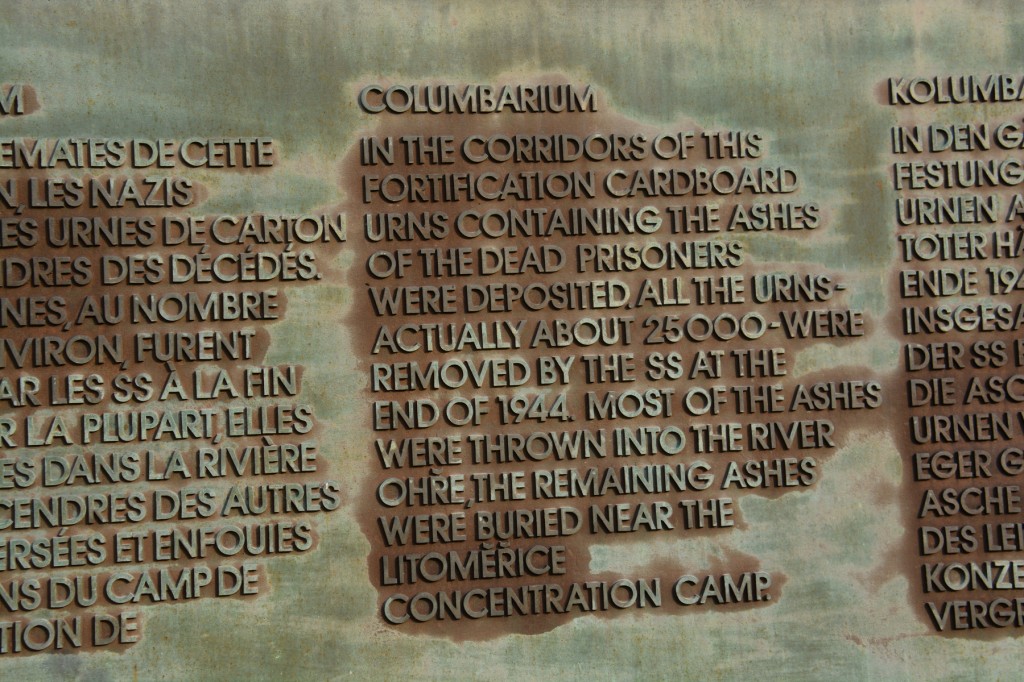

Even farther outside the town, I found the old Crematorium (by following the somewhat creepy directional signs featuring a Jewish star–”this way to the Krematorium Jews!”). While at first the Jews were allowed to bury their dead, eventually there were too many and cremation became standard procedure. Towards the end of the war, the Nazis dumped all the ashes in the river, worried that the sheer amount of death would be discovered.

But, that’s the ultimate horror of Terezin. A place this evil with this much death can’t be hidden. And, maybe that’s the point of visiting. Terezin didn’t just terrorize Jews; it has an unbroken history of evil nearly 300 years long. The standard way to close an essay like this is with the phrase “Never Forget” lest history repeat. Well, history has already repeated several times at Terezin and even if the people forget, it will be a long time before the place forgets.

Photo Gallery

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

“Work will make you free” slogan painted over the entrances to many Concentration Camps

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-